By Alex White - Co-Head of ALM, Gallagher

And unlike most other financial instruments, there’s a remarkably clear relative value signal between government and corporate bonds. Buying corporate bonds instead of government bonds means taking default risk, pricing risk (in spreads) and illiquidity risk (though IG is normally liquid, this can dry up in a troubled market). For the UK market specifically, there is also contagion risk (in that if anything goes wrong in any one of the gilt, UK DB, or UK IG markets, they’re so interconnected that any rot could spread very quickly to the other two); for foreign currency bonds, there are FX hedging, rebalancing and collateral risks too.

Investors need to be paid for taking these risks, and they generally are- the spreads are positive, and generally provide enough to both compensate for the risk and earn a return. But there is clearly a price at which it stops making sense, if not for all investors (eg for those with particular tax incentives), then at least for those with fewer constraints. If the spreads on IG bonds were negative, we would expect DB schemes to sell their holdings, for example.

So where is the level at which it stops making sense? And are we through it now?

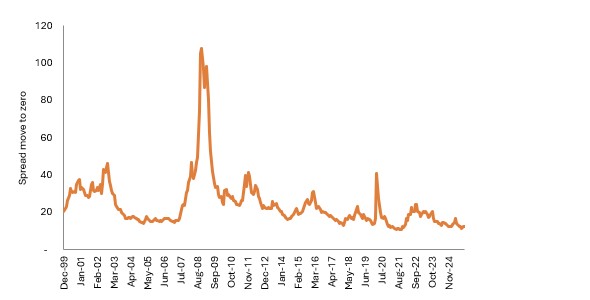

Source: Data: ICE; Calculations: Gallagher

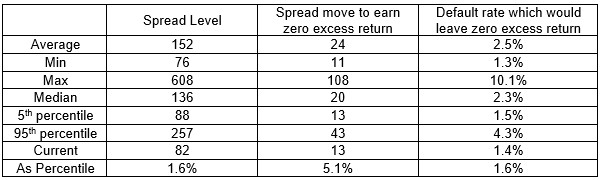

One way of looking at it is to reverse the question- what needs to happen to wipe out all the excess returns? The wider the spread, the better the price, and the more headroom you have to soak up losses. Right now, there’s not much- in fact, a 13bp move over the year would wipe out all the excess returns. For context, IG spreads have moved by at least 13bps over a year 76% of the time[1]. For 98.4% of the history (since 2000), investors have been better compensated than they are today. We are not at quite the worst spread levels ever seen, but current levels are close.

Source: Data: ICE; Calculations: Gallagher. Index is C0A0 – US all IG. The bottom row shows the current level as a historical percentile- eg only 1.6% of the time have spreads been lower than current levels.

There are those who will counter that spread widenings don’t matter, because if you hold the bonds to maturity you still earn the spread. There are complications here, especially around collateral and FX, but to whatever extent you can hold bonds to maturity the same logic around tight spreads applies to default rates. On average, investors could have managed a default rate of 2.5% (assuming 40% recovery rates) and broken even. Currently that buffer is just over half the size, at 1.4%. That’s not an unreasonable number of defaults- for context, 6-7 year BBB default rates have averaged about 3%.

But even if they don’t, we’re quite likely to see a widening in spreads; if we don’t, it probably means every risk asset would have done well anyway. If we do, then at that point investors who had held less in credit would have more firepower to buy bonds when prices lowered. And to earn returns of c1%, there are no shortage of good options, especially as you can replace £100 of IG with (say) £30 of something higher returning and £70 of cash. As a starting point, three of my personal favourites are:

Put-spread selling (c50-70% exposure needed)Absolute return rates funds (c30-50% exposure needed)ILS (in much smaller quantities, only about 10% as much exposure would be needed)

All in all, as spreads creep lower and lower, investors must eventually reach a price at which IG credit just doesn’t work anymore. If you think we’re nearly there, then it’s probably a good time to think about diversifying the first 10-20% of your IG holding.

[1] Source: Data: ICE; Calculations: Gallagher

|