By Alan Greenlees, Senior Consultant, XPS Pensions Group

There are numerous types of risks that can impact schemes but grouping them into rewarded and unrewarded risks is a simplistic yet appropriate approach, as it helps frame possible action:

• Rewarded risks are a fundamental means to generate investment returns such as equity risk or credit risk. They are risks associated with the expectation that over time they will lead to profit to the investor. Diversification is a key tool in the effective use of rewarded risks as it allows the reward to be retained whilst reducing risk.

• Unrewarded risks might lead to a profit or a loss but are not expected to deliver a profit on average, such as interest rate risk. It is important to seek to remove the unrewarded risk as far as possible from the portfolio but in this instance, diversification is not the right answer because ultimately the exposure will still contribute some risk to the portfolio but for no expected reward.

There are nuances though – some risks sit somewhere in between the two definitions above. These can be risks that are inherent within running a pension scheme, but are expensive to remove or hedge. An example of this is longevity risk – the risk that your membership lives longer than the Actuary is assuming, increasing the cost of paying pensions. In this case longevity might be considered a rewarded risk, and therefore beneficial to retain in part.

Additional risk factors such as Environment, Social and Governance (ESG) and operational and counterparty risks can be difficult to quantify. However, direct management and mitigation of these risks at a granular level is often required, rather than simply hoping they’ll be ‘diversified away’ in the wash.

Risk measurement – keeping a clear line of sight

It can be useful to estimate risk, such as looking at the commonly used 1-in-20 year downside risk. However, this ‘Value at Risk’ assessment is not a panacea for risk management. The reality is that risk is not black and white – how many things in life can be summed up in one number?

Pension scheme portfolio construction has evolved considerably over the last 20 years. Across the industry an initial focus on manager diversification alone has progressed to a more robust focus on asset class diversification. But still some elements of the recipe are misunderstood.

For instance, asset class diversification in itself is not necessarily beneficial in all circumstances. As an example, holding a combination of equities and bonds issued by the same company does not diversify this source of risk – it just changes the return you’ll earn in good and bad scenarios for that company. True diversification comes from gaining access to other drivers of return – in this case introducing exposure to more companies.

Diversification – know your limits Diversification – know your limits

The belief that you can make a portfolio better by continually adding assets that are less than fully correlated to the portfolio is overly simplistic. If this was true you could always add something to improve a portfolio – which you can’t.

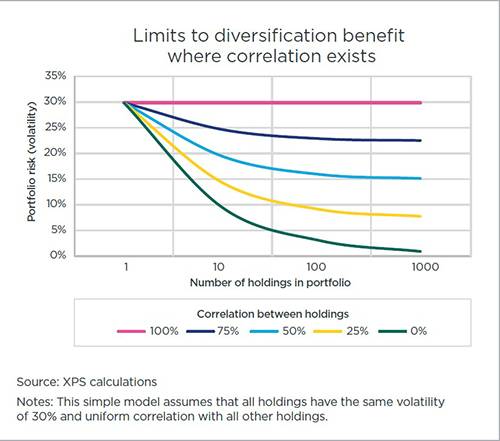

This is partly because diversification usually involves cost but also because correlation between assets means there are limits to diversification.

In fact, correlation between assets is a significant factor in the limit of diversification.

Increasing the number of holdings does not necessarily lead to a meaningful reduction in risk.

The Credit Crunch in 2008 was a living memory example of where underlying correlation between systemic risks was overlooked by many investors. Within equities, correlations rose above 50% relative to average historic levels of around 25%. This can significantly compromise diversification benefit – almost doubling the modelled risk.

Risk has many dimensions. Therefore, the most reliable way to measure and manage it is to assess it from as many different angles as possible. Ultimately, schemes should look to avoid any concentrations of risk within any particular dimension. It is only on closer inspection that we are able to identify the red flags and assess how the strategy can be improved.

Conclusion

A truly diversified strategy, across multiple levels, should be a goal for all schemes, large and small. Identifying the potential pitfalls within a strategy enables Trustees to make informed decisions regarding the level and type of risks that the scheme is exposed to.

Trustees should have a clear understanding of how their scheme looks from a multi-dimensional perspective which should help to provide confidence in the portfolio’s resilience to any particular risk driver.

|