By Alexander White, Managing Director, Co-Head of ALM, Redington, a Gallagher Company

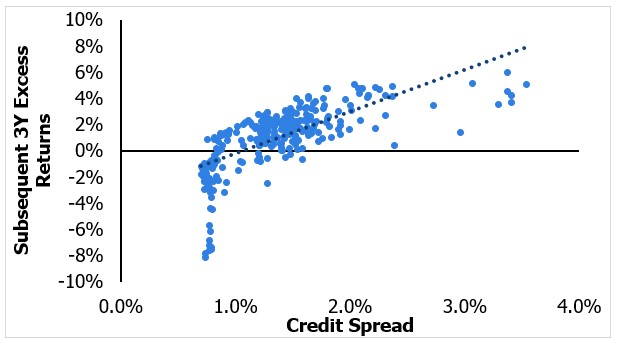

Firstly, when spreads are low enough, it’s likely investors will lose money.

This chart, which is based on long-dated (10+) UK debt (ICE UC9S) shows that the lower spreads are, the more likely the index is to lose money. This is both because spreads typically show mean reversion and because there’s no carry to act as a buffer.

Source Data: ICE

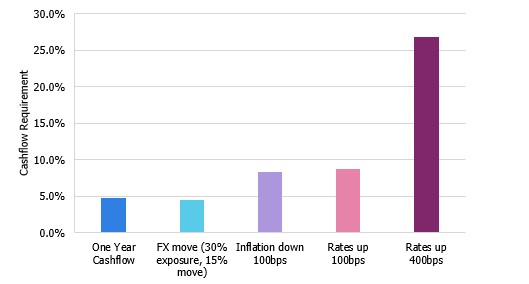

When spreads are low, a lot needs to be invested in bonds to get any return. This means more money and risk, and holding less cash. For a DB scheme, the result is less resilience to any unexpected cashflow requirements which can come from several angles, particularly LDI and FX hedging. Below, we illustrate what these shocks entail for a typical well-funded DB scheme holding 60% in IG (which reduces the sensitivity to rates by about 25%) under various stresses.

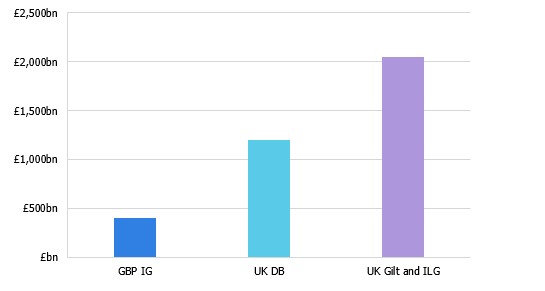

Holding less cash increases the risk of being a forced seller of assets - and that’s made worse by contagion. In other words, if you’re selling the same stuff as everyone else, you’ll get a worse price; a problem which is amplified if the market is small.

The entire Sterling IG market is worth about £400bn (ICE UC0S), as against roughly triple that of DB pensions. So, without even considering insurers, DC, and other debt holders, this is a heavily overbid market. In 2022, we saw how the closely tied gilt and DB markets created a negative feedback loop, and the gilt market is £2trn and much more liquid.

Source: ICE, PPF

So, what to do?

Buying IG has become increasingly unattractive, but the core characteristics, such as contractual cashflows, have an appeal.

Is there an alternative that looks similar but avoids a lot of these problems?

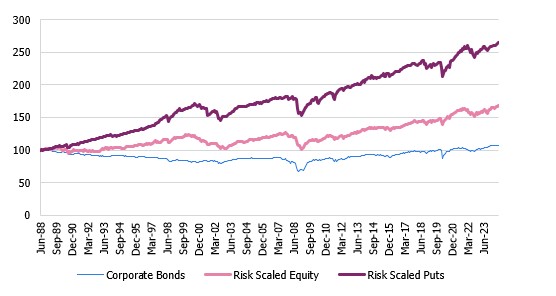

To answer this, let’s first consider what a corporate bond really is. A corporate bond typically pays a known, fixed amount most of the time, and occasionally gives a large negative return. Conceptually, it’s a lot like a put option (the Merton model actually uses this to price bonds as put options on the EV of a company). So, you might expect similar performance, but that’s not always the case. Looking at US all stocks IG (ICE C0A0), the S&P500, and the Bloomberg PUT index, credit has performed pretty badly for about three and a half decades. Even scaling down for risk (matching the IG volatility), put selling has performed far better, and has outperformed equities on a risk adjusted basis.

Source Data: ICE, Bloomberg

There are plenty of differences (for example in sectors) and several technical reasons why passive investing is not the ideal approach for buying credit, but with such a large gap, the simplest explanation is that lots of investors want to buy bonds, but few are willing to sell puts. It’s not an arbitrage, but is this at least an opportunity?

Selling puts has plenty of advantages over IG. It offers better historical returns, much better liquidity (based on index options), and it has no contagion risk with the UK DB market. For the same level of return, at current spreads, the exposure would be significantly lower and potentially lower risk. However, selling puts comes with considerable tail risk. So, what if you sold put spreads? Basically, you sell a put (say 1million at 97%), then buy one further out of the money (say 1million at 93%). In this example, the worst month you can possibly have costs you about 3.5% (you get a 4% loss on the payoffs, but you still get the premiums), for a roughly 6-8% yield per annum. The monthly payoff chart would look like this:

Moreover, once you buy the second put, you can leverage it modestly, say 3-4x, since the option gives you significant protection. This allows you to free up more cash, so you have an asset which:

• Frees up cash

• Has far better downside protection than IG

• Has no contagion risk with UK DB, and

• Has full daily liquidity

The trade-off is a degree of complexity, and the actual implementation can be far more sophisticated. But the basic concept is fairly simple, and it addresses many of the key weaknesses of IG, especially when spreads are as compressed as they are now.

|