By Alex White, Head of ALM Research, Redington

In one sense this is true. At any point in time, the aggregate portfolio will be the market portfolio. But this misses a key detail. Not every active investor is an active manager. Investors with structural home biases, for example- and retail investors holding personal portfolios- are, in this sense, active investors. Unless there is truly no information to be had, it is hard to see that these investors are competing on a level playing field against a well-equipped and resourced team of professionals.

So what does the evidence say? There is empirical evidence that active management can lead to positive returns. Looking at the 20 year period from 1997 to 2017, the Morningstar database suggests 31bps of net alpha from 1.65% tracking error; the eVestment database for institutional equities implies 1.16% of net alpha (with 0.5% fees assumed), for 1.42% active risk (sources AQR, Morningstar, eVestment).

That these values are so different is something of a flag. At least part of the explanation is likely to come from survivorship bias.

Essentially, managers will grow more, attract more investors, and publish their results more freely if they’ve had strong performance. Those with weaker performance are more likely to fail, and thus disappear from the records. In particular, the eVestment database is self-published, so is likely to suffer from more survivorship bias.

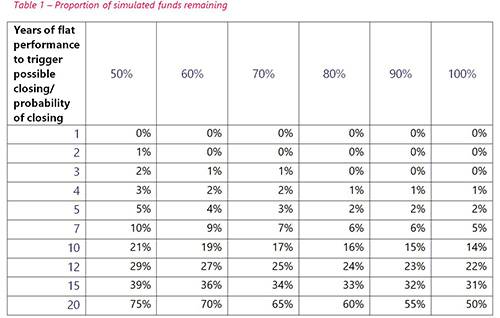

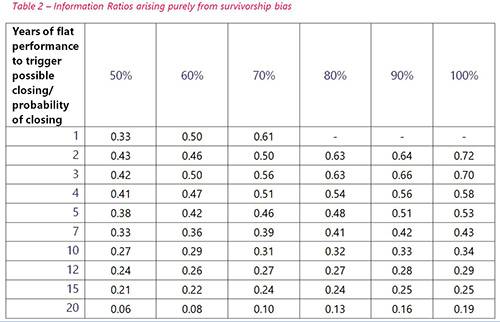

So we should haircut the evidence, but it’s not obvious by how much. However, we can test this, at least in theory. Assuming a logistic distribution (essentially a normal distribution but with fatter tails, and simpler computationally) for alpha, we can simulate 10,000 funds, with volatilities in line with the history, expected returns of zero, and prescribe rules for when funds fail. Essentially, we ascribe an x% chance (at the end of each period) of excluding any fund that has a period of n years with negative total active performance.

Clearly, this won’t solve the active-passive debate. But it does show a few things. Firstly, that survivorship bias can be significant; but also, for it to explain a 0.2 Sharpe entirely, we would have to see a fairly punchy half to two-thirds of the original funds drop out of the reckoning. It seems unlikely that survivorship bias could explain all the alpha.

|