By Matt Tickle FIA, Partner at Barnett Waddingham

The policy response so far – central banks

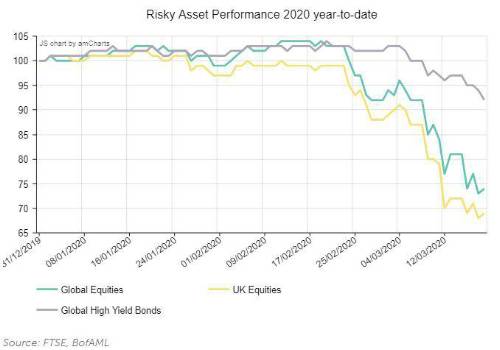

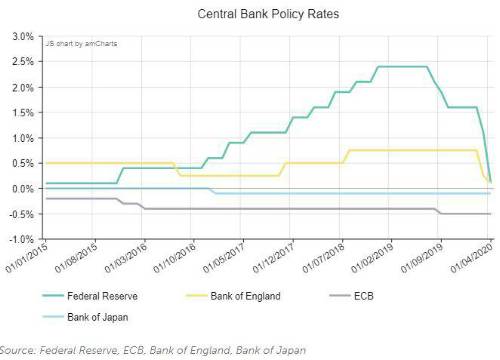

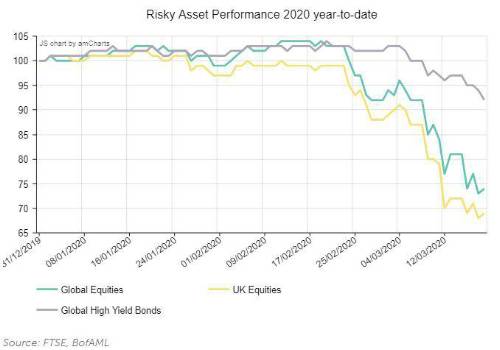

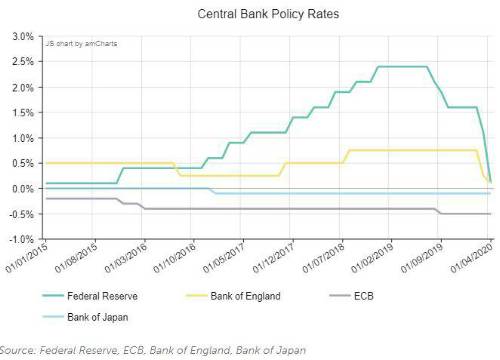

The Federal Reserve kicked off a wave of central bank and government intervention on 3 March, cutting US interest rates by 0.5% from a range of 1.50-1.75% to a range of 1.00-1.25% – its first such emergency move since the financial crisis. The UK followed suit on 11 March as the Bank of England also announced a 0.5% emergency rate cut from 0.75% to 0.25%. However, these emergency measures did little to stabilise stock markets, with government bond yields hitting new all-time lows and major equity indices falling into bear market territory (20% falls from their peaks).

Markets continued to tumble and volatility surpassed its previous peak during the global financial crisis. It was clear that investors were still concerned about the impact of Covid-19 on the global economy.

On 15 March, the Fed acted again, this time slashing rates by 1% to a range of 0-0.25% and announcing at least $700 billion of purchases of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities in the coming weeks. The Bank of Japan also eased policy in an emergency meeting, ramping up purchases of exchange-traded funds and other risky assets. The Bank of Japan Governor did however say that he doesn’t “think we have reached a limit on how deep we can cut interest rates, and if necessary, we can deepen negative rates further.”

The ECB also announced measures to support bank lending and expanded its asset purchase programme by €120bn. However, Christine Lagarde, President of the ECB, did disappoint markets by not cutting rates, which many market participants had expected. She also suggested that the ECB would not intervene to stabilise sovereign credit spreads, as they had done during the Eurozone crisis. The ECB was forced to clarify this mistake on 19 March, by announcing a further €750bn euros of asset purchases to be conducted this year. The Bank of England again flexed its muscles on 19 March. It made another emergency rate cut, this time to 0.1%, and also announced a further £200bn asset purchase package, the majority of which will be used to purchase government bonds.

The policy response so far – fiscal stimulus

As it became clear that monetary policy was having no significant impact on financial markets, governments realised that more fiscal policy was necessary. Indeed, in our view, this was always vital and should have been the first, not second response. The UK Budget on 11 March, where Chancellor Rishi Sunak unveiled a £30bn fiscal stimulus package with £12bn specifically to counter the economic effects of Covid-19, however, proved to be a bit of a damp squib.

Therefore, on 17 March, Rishi Sunak unveiled an unprecedented stimulus package including a £330bn loan scheme to support businesses, in addition to a number of direct measures including tax cuts, millions in grants and mortgage holidays. This again had little impact on markets and it seemed more was required. And on 20 March, it seemed a more fitting response was delivered. This time, Rishi Sunak announced a giant economic rescue plan. The headline measure was that companies were told that the state would pay 80% of wages up to £2,500 a month for workers who would otherwise have been made redundant. The government will also inject £7bn into the welfare system amongst numerous other measures amounting to a £30bn injection of cash into the economy.

Even the White House is proposing a stimulus package of up to $1trn to help soften the blow of a sudden recession on individuals and businesses. At this point, what more can be done to support the economy as Covid-19 continues to spread?

What more?

From a central bank perspective, their ammunition lies in further rate cuts (see below for our Research Team’s outlook for UK base rates), taking more central banks into negative territory, and further quantitative easing. Major regions including the US and the UK could join the likes of the ECB, Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden and Japan, all of which have already resorted to adopting negative rates. The aim of this unconventional policy measure is to encourage banks to lend more, with the hope of jolting a sluggish economy because they would, hopefully, lend at a low interest rate rather than pay to keep its money at a central bank. Further quantitative easing also remains likely.

There is scope to do this but it will likely mean moving from buying just government bonds, back to buying more asset-backed securities, corporate debt and possibly even equities like the Bank of Japan. Intervention on this scale will likely have an impact on asset class pricing.

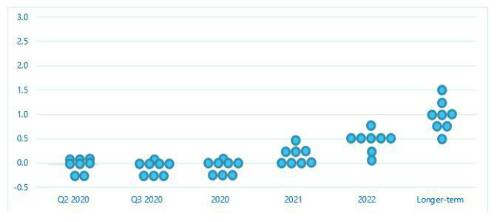

Barnett Waddingham’s Research Team: UK base rates dot plot, as of 20 March 2020

Each dot represents one member of the Barnett Waddingham Research Team. The dots reflect what each individual thinks will be the UK base rate at the end of each stated period. On the Y-axis is the UK base rate, and on the X-axis is the period for which individuals gave their forecast.

What will likely be a more important factor in decreasing the negative implications of Covid-19 is further and coordinated government action. We have already seen significant government measures around the world but there is definitely scope for more to come. This includes the form of more loans to businesses, more tax cuts and longer mortgage holidays. Another method is helicopter money (direct payments to citizens), a measure which has been well received in Hong Kong where permanent residents aged 18 and above will each receive an HK$10,000 (£1,100) cash handout to ease the burden on individuals and companies. The US is also discussing a similar plan.

What Next?

It’s clear that more needs to be done to save the global economy from a deep and prolonged recession. It’s also clear that there may be more that central banks and governments can do. Ultimately, whatever measures are taken, they will have long-term implications on the economy and financial markets. Look out for our next Insights Note in the second half of April, where we will discuss the long-term implications of the crisis and the central bank and government actions taking place to tackle it.

Chirag Jasani, research analyst at Barnett Waddingham, contributed to this article.

|