By Alex White, Head of ALM Research at Redington

If enough stockholders believe a stock will fall, and either sell it or short it, the price will fall. It may become a good value stock as a result, and reward those who hold it or buy it, but the price will fall. That means economic theories are vulnerable to regime change in a way that gravity isn’t, which makes it harder to test.

One theory in vogue now is that stocks have performed well recently and valuations appear high because rates are low. The idea is that future value- ultimately, future dividends -should be discounted less heavily. It’s plausible and coherent- but is it true?

We know there should be some one-directional effects because lowering rates has been used as a policy tool after crashes, alongside stimulus packages. That is, equity crashes may now make rates falling more likely. But do lower rates drive higher equity prices?

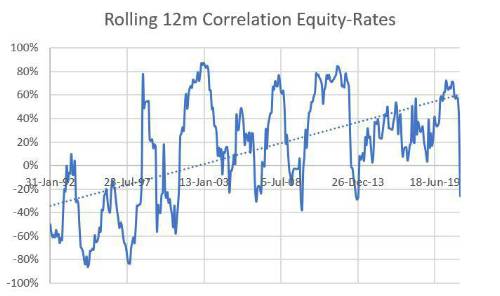

The simplest test is to look at correlations, and it’s not very strong. The correlation since 1994 between US 10y government rates and the S&P 500 has been 14%. High rates might indicate strong growth environments, which would appear to be a stronger factor. Even if we look rolling correlations, the trendline is actually the other way around, albeit with a lot of noise. So are higher rates good for equities?

Well perhaps- there are, after all, a lot of other factors involved, not least regulation. A better test would be something simultaneous, reflecting the closest analogy to a control group. Can we do this?

If the dividend theory is true, we might expect the impact to be lower on high dividend stocks. This is because stocks paying higher dividends today should be expected to pay less in the future. So, in theory, high dividend stocks should be less sensitive to rates than the wider market. Are they?

Maybe. The correlation between high dividend equities and rates has been 2%, so smaller, albeit with a fair degree of noise around it. Set against that, high dividend stocks have outperformed even as rates have fallen and broader value factors have struggled.

This doesn’t disprove the theory. It’s also not an entirely rigorous test, and there are plenty of other possible explanations. What it does, however, is suggest that if it is true, it’s only very recently become meaningfully so. Discounting dividends gives a simple, coherent, elegant theory- but it’s not obviously backed up by the data. Maybe it’s time to bag it up.

|