Jenny Gibbons, Head of Pensions Governance, Nicola van Dyk, Governance Generalist and Catherine Ryder, Governance Generalist at WTW

The term most often seems to be invoked to mean “lighter touch”. But it’s important to consider that proportionality works both ways – demanding more in some areas even if less in others - and seeing it purely as an opportunity to scale back ambitions runs the risk of missing out on valuable opportunities to make improvements, or the risk of failing to meet TPR’s expectations. The key, for us, is focussing your efforts in the right areas.

In this article we’ve considered how a proportional approach to compliance with the General Code might be applied to a fully bought-in scheme, and how to adapt your governance journey plan for your scheme’s circumstances.

Fully bought-in schemes transitioning to buyout

The Regulator has been very clear that the expectations of the Code still apply to fully bought-in schemes – there will be no free passes for trustees in these circumstances. And, we’d argue, the need for a proactive and nimble risk management framework and robust Effective System of Governance (ESOG) is as sharp as ever.

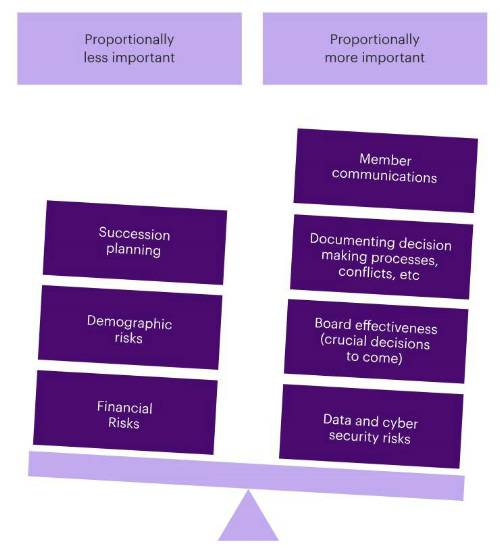

While a full buy-in mitigates many of a scheme’s financial and demographic risks, a large number of operational and administrative risks remain. Some risks are arguably exacerbated; for example the transfer of member data from the scheme to an insurer can lead to additional data and cyber security risks. Furthermore, trustees of fully bought-in schemes that are nearing their endgame will need to make irreversible decisions about the future of the scheme that will have a direct impact on members. It is therefore more important than ever to give heed to those parts of the Code that relate to decision making and communications.

Trustees of fully bought-in schemes that are nearing their endgame will need to make irreversible decisions about the future of the scheme that will have a direct impact on members.

Focussing in on decision-making, the General Code states that trustees should “have enough skills to judge and question advice or services provided by a third party” and that they should “regularly carry out an audit of skills and experience to identify gaps and imbalances”. Transitioning from full buy-in to buy-out is a significant project often involving a range of activities that many trustees will be unfamiliar with, such as negotiating with the sponsor and making decisions on the use of residual assets, dealing with member representations or seeking insurance protection for trustee liabilities post wind-up. It will be important to review the skills and experience within the trustee board to establish any gaps ahead of a critical period of decision making (and to arrange for focused buy-out and transaction training where necessary).

From an operational perspective, good record keeping in which there is clear documentation of decision-making processes, delegations and the way in which any conflicts of interest have been managed will also be important for trustees to protect themselves from the risk that their decisions or approach are questioned down the line.

And finally, winding up a scheme brings with it particular member communication requirements. The General Code states that trustees should “ensure that all communications sent to members are accurate, clear, concise, relevant and in plain English” and, of course, that they comply with legislative requirements in relation to timing and content (which are more onerous if any residual assets are to be returned to the sponsor).

Figure 1. Change in balance of governance priorities for a fully bought-in scheme moving to buyout

Adapting your governance for your circumstances

From the example above it is clear that governance should continue to be a priority for fully bought-in schemes transitioning to buyout. But how should schemes look to adapt their governance according to their individual circumstances?

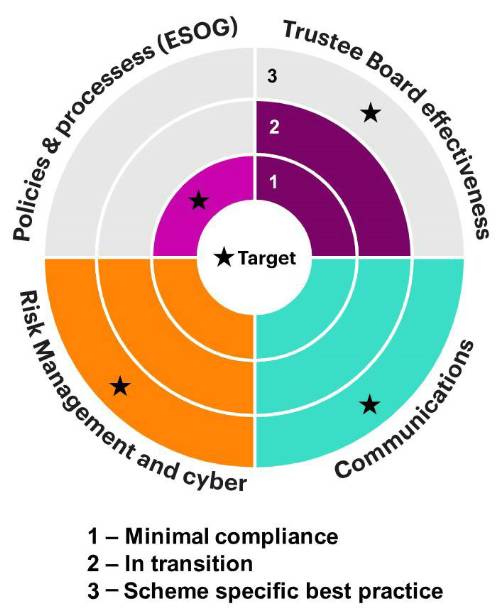

While each situation will be unique, we would encourage trustees to consider where they are and where they wish to be on their governance journey. This provides a framework within which to prioritise governance activities.

Figure 2. A sample prioritisation framework (client specific examples would include scheme specific descriptions in each cell)

Even within the categories listed in figure 2 there will be opportunities for prioritisation – for example bringing forward those ESOG policies and processes that do the most ‘heavy lifting’ for the scheme or deferring further review of those that have been looked at relatively recently. And, of course, ‘efficiency’ forms a useful complement to ‘proportionality’ – so schemes can ask their advisers for tailorable policy templates, inexpensive ESOG front sheets (like our ESOG HomeSpace ) and simple and accessible risk register formats to make Code compliance easier.

Conclusion

It’s clear that many schemes are at a critical point in their governance journeys. With endgame on the horizon for some, bringing with it important decisions about the future of the scheme, proportionality should not equate to complacency. Honing in on the areas of the Code that are of most relevance, such as cyber risk and governance, improving trustee decision-making, and enhancing member communications, could be key to obtaining the best outcome for members and trustees alike.

And whilst there isn’t (and shouldn’t ever be) a one-size-fits-all approach, taking a step back to consider how your governance journey plan can best support your wider scheme objectives will be time well spent.

If you have any questions or would like to discuss the General Code further, please contact your WTW consultant or one of the contacts below.

Contacts

|