By Hartej Singh, Head of Public Credit at PIC

By the end of the year the majority of the world’s stock exchanges were up, particularly in the technology sector, because companies also made more profit, despite high inflation. Economic activity continued with less drag than expected from higher interest rates and inflation measures reduced to more normalised levels, albeit still at a level higher than the last decade. However, higher interest rates typically take 18 months to be felt in the wider economy, and 2023 might therefore have been the calm before the storm.

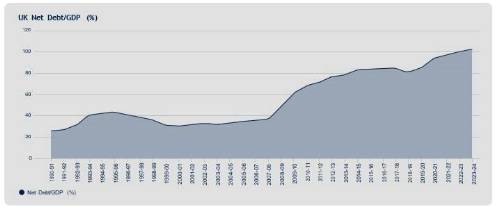

Part of the stronger economic activity we have seen has been funded by additional government spending. The UK has the highest UK Net Debt to GDP ratio since WWII when it topped over 200%, and the highest tax burden for more than 70 years. Whilst sovereign debt sustainability is not generally talked about, although the outgoing head of the Debt Management Office is now on the record warning about this, we expect a mixture of higher interest rates,

an ageing population, and little room for more tax increases, to mean this number will continue to rise.

To stabilise the debt to GDP ratio, whoever is in government will need all, or a combination of controlled higher inflation, low gilt yields, (even) higher tax revenues and less government spending.

One prospect not currently being discussed is that, if and when inflation is under control, we might see a reversal of Quantitative Tightening and more Quantitative Easing and other extraordinary monetary policy measures to bring down borrowing rates and help the UK finance its large debt load.

We are likely to see elections in not only the UK, but also large population centres like US, India, Mexico, Bangladesh, Indonesia and Pakistan. This not only has both national effects but also international effects and the relationships between countries is becoming more important.

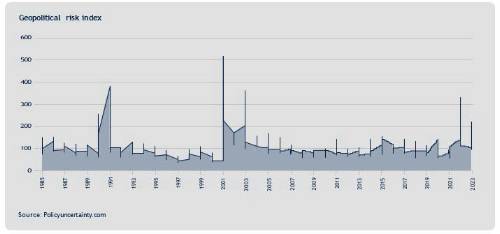

Geopolitical risk feels like it is rising. To qualify that statement, I think a good working definition is an increase in hostile interactions between countries.

This is not just in terms of open conflicts as Russia/Ukraine and in the Middle East, but also in terms of significant changes in trading partnerships and supply chains for economies. This will likely be more of a problem for

long-term investors than is currently recognised.

Whilst it is tough to be objective about geopolitical risk, there is an index we look at which measures which proportion of stories in newspapers have some reference to geopolitical risk. That, at least, tells us if geopolitical risks are being talked about, so a proxy of sentiment.

Geopolitical events like 9/11, the Iraq and Afghanistan war, the Russia and Ukraine war, and the Gaza conflict, are front and centre for a period, but then very quickly both the world and the markets start to discount the impacts. Soon they are relegated from the front pages. The problem is when they drift on with no discernible outcome.

In my experience, the markets would prefer a ‘bad’ certainty which they can price, than general uncertainty which they can’t, or at least they tend to behave that way. From our perspective, taking a gamble on geopolitical events, or anything else, is not an investment strategy that sits well with our purpose, of paying the pensions of our policyholders.

But underlying the big shocks, are the longer-term, less reported impacts of geopolitics, which we also need to consider. Let’s take Germany as an example. Germany has been impacted by two large geopolitical changes. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to Western nations sanctioning Russia.

This impacted Germany’s material energy dependence on cheap Russian natural gas supplies.

Additionally, Germany has also built a large part of its economy on exports to China. Whilst there are many contributors to China’s lower than trend growth, the US/China tariffs and technological sanctions mean that Germany is directly impacted by the US/China face-off. These impacts mean that capital markets, technology sharing, and resource supply might decouple, leading to supply chains being refocussed amongst allied nations, rather than truly global trade. This is likely to have economic ramifications as a less-than-orderly – or perhaps openly-disorderly in the event of a further escalation. The pace at which companies retreat from China may pick up pace.

Geopolitical risk is taking up more and more of my time as I seek to manage our portfolio, and is probably at its highest level in my 20+ years in the markets. Companies that have large resource, manufacturing or sales exposure to countries that could be at the centre of hostilities are running very real geopolitical risk – this might in the future impact credit profiles and change our decision on a new or existing investment.

|