By Alex White, Head of ALM Research at Redinton

Firstly, this is only considering investments. You can apply the lens of anti-fragility to ideas, individuals, careers, cultures, and so on, and what’s desirable or practical can vary wildly in each. It is worth noting though that, all else being equal, anti-fragility is useful if you want the anti-fragile thing to persist; but that may not be the best outcome.

For example, war is surely more anti-fragile than peace, in that it takes less to start a war than to end one.

Antifragility may be a useful lens to see how viable a system is, but it cannot be the whole goal. In investment, however, the goal is typically maintaining and growing a portfolio to some end, and I’m deliberately simplifying the scope of the problem.

Secondly, doing well when things change, all else being equal, has to be desirable; the question is one of cost. It’s not quite true that there are no free lunches , but relying on them has rarely been viable over the longer-term. If it costs too much when things don’t change (or don’t change by enough, or change in a way you didn’t consider), then the theoretically lovely anti-fragile investment may be a poor one in practice.

In some ways, this is what a risk premium is. Equities will probably go up, but crash periodically. Investors are rewarded for taking the risk- or, more prosaically, equities go up because they sometimes go down. Equities are fragile investments, but have proven to be excellent investments for a wide range of investors.

If we extend this, we can think of several fragile investments, and several industries where each individual firm should be fragile. In no particular order:

• Insurance companies

• Shipping

• Money-Lending

• Any specialised industry

• Mortgaged home ownership

• Debt/Leverage

No investment is right for every investor, but any firm in some of the oldest, most reliably established industries must be fragile (whether the oldest profession is anti-fragile or not is less clear). If an industry has functioned for centuries then it shouldn’t be dismissed too readily. Airlines- cited as an anti-fragile industry- are certainly faring worse.

Airlines are actually quite an informative example. The industry is anti-fragile, in the sense that each crash provides data and improves the next plane (so it may be slightly unfair of me to cite it as an example of anti-fragility here). However, the industry has proved fragile to a totally different threat- namely a sudden, legislated stop in demand. This shows that fragility and anti-fragility can only be seen relative to the threats you can think of. If you’re paying a lot for anti-fragility, you may well actually still be fragile, and just underweighting the unknown unknowns.

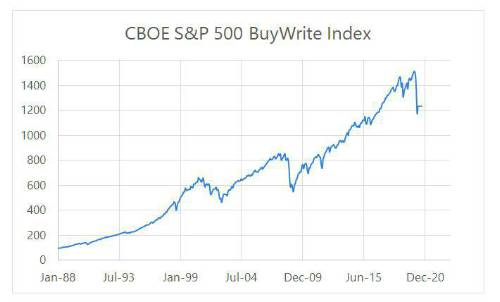

Like holding equities, writing options is fragile (while buying them is antifragile). Options can have spectacular payoffs. Generally speaking though, analogous to insurance products, they’re priced such that buying options tends to cost more than it earns. For example, the CBOE S&P500 BuyWrite index (shown below) tracks the performance of a simple strategy writing covered call options. This doesn’t mean investors shouldn’t use options (nor that individuals shouldn’t use insurance!)- it just suggests that anti-fragility may be an unrealistic goal for a whole portfolio.

Similarly, while value stocks have endured a horrible decade, the more established value-biased and quality-biased (boring) stocks have historically outperformed smaller, exciting, growth stocks (especially when beta-adjusted). This again suggests the premium for dramatic upside can be punitively high.

All this presents anti-fragility in quite a negative light, and it’s worth remembering that the concept has a lot going for it. Individual firms will eventually go bust, but the stock market continues- this can be seen as the anti-fragility of investing in a basket. Fragility is almost certainly easier to gauge than the future is to predict, and being risk managed can often turn out better than being almost entirely right. Being too fragile is effectively the same as running too much exposure to one risk, and investors should aim to avoid this. However, the simpler approach of diversifying a portfolio and limiting fragility, while accepting some losses during downturns, may be more profitable over the long-run than aiming for the more ambitious and expensive goal of explicit anti-fragility.

|