By Richard Butcher, Managing Director at PTL

This blog considers a near horizon item – the consolidation of pension schemes.

There is a good quote on consolidation by Thomas Jefferson (the third president of the United States) – but I’m going to save it until the end of this blog. I need to build up to it.

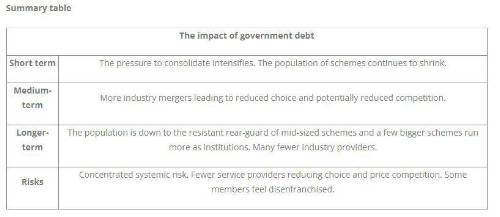

Pension scheme consolidation is already happening. The number of DB schemes has reduced from 7400 in 2007 to, currently, around 5,400 (source: PPF). The number of DC schemes with more than 12 members has reduced from around 4,500 in 2010 to around 1,740 in 2020 (source: TPR). But will this continue and if so why? And what risks does it create?

The concept of pension scheme consolidation is, on the face of it, already well known but let’s define it anyway.

In a DC world, consolidation describes the transfer of smaller, usually single employer, pension schemes into larger pension schemes and, currently, mostly DC master trusts (DCMTs). As a result of master trust authorisation, it has also extended to mean master trusts transferring into other master trusts. The receiving master trusts are all, essentially, of the same model.

In a DB world it describes the transfer of, again, usually single employer schemes into (a) the PPF, (b) an insurer (using their buy-out product) or (c) a DB master trust (DBMT).

The DBMTs come in two flavours. The traditional master trusts have been around a long time, and their proposition is “we’ll give you economy of scale and reduced operating costs” – generally they’ll also have centralised governance. The new generation of master trusts aim to offer a proposition which is “we’ll do all of that, but we’ll also accept the covenant risk as well”. The other critical difference is that although there are two new generation DBMTs notionally on the market, neither has yet won any business that they’re telling us about, although both claim strong pipelines.

So, if that’s what consolidation is – why is it happening?

In the case of buy-out, the driver is the corporate wanting to de-risk. In the case of the PPF, the driver is the corporate having taken too much risk!

In the case of consolidation to larger schemes, including DCMTs and DBMTs, the drivers are, broadly, the same: scale (a) reduces unit costs and (b) increases opportunity (for example, access to a wider range of assets) and, generally, according to TPR research, bigger schemes tend to be better governed than smaller schemes (although this isn’t exclusively the case). In the case of the new generation DBMTs the putative argument is also the opportunity for the sponsor to de-risk.

But there are a couple of other drivers as well – implied rather than explicitly stated. The government is keen on consolidation because larger schemes are better able to invest in illiquid assets. The Prime Minister and Chancellor recently called for an “investment big bang” – urging pensions schemes to invest in the UK economy to support Build Back Better. This will be easier if there are fewer, larger schemes. The regulator is keen on consolidation because, firstly, their research suggests less resultant risk, but secondly, because they’ll end up with a smaller regulated population – allowing them to focus their resources.

All of this is leading to an increasing amount of pressure on trustees to consider consolidation. In DB by having robust de-risking plans (no bad thing) leading to low or no reliance on the sponsor, in DC through greater focus on the VFM test and, in some schemes’ cases, an explicit legal requirement.

But there are potential down sides to consolidation.

In a consolidated scheme, the governance is further away from the member. This isn’t inherently bad, but it does feel more sterile and remote. Ultimately, pension schemes are all about the people. We shouldn’t forget that.

There is a risk of diseconomies of scale. As a scheme grows, its ability to reduce costs slows. Also, larger schemes can move markets, meaning they can’t always buy or sell at the best price.

Then there are the systemic risks. We learnt during 2008 about the risks of banks getting too big – the same could happen to pension schemes. We diversify in our investments to de-risk. Consolidation could lead to focused risk.

Bigger schemes are going to be more susceptible to political pressure (maybe to build back better) which may or may not be a good thing. I’m not suggesting they’ll give in to that pressure, but it will take something to withstand it.

Finally, the impact on the pensions industry. If there are fewer schemes then we need fewer actuaries, lawyers, auditors, and even fewer professional trustees. Now, to be clear I’m not arguing against consolidation to save the pensions industry, I’m merely making the point that consolidation threatens the sustainability of those serving the market.

And so to my Thomas Jefferson quote: “Our country is now taking so steady a course as to show by what road it will pass to destruction, to wit: by consolidation of power first, and then corruption, its necessary consequence”.

Consolidation is not a one-way street to good things and, as a result, there is something of a rear-guard action happening. Many mid-sized schemes are determined to remain well governed and well resourced, but unconsolidated.

Up periscope – looking to the horizon

|