By Alex White, Head of ALM Research at Redington

Given recent high inflation, deflation, and especially long-term breakeven rates below zero, do not seem likely. They’re probably not a high risk on many schemes’ radars. But the recent history of rates should tell us to be careful. Many thought both real rates and nominal rates would always be positive before they went negative- indeed, the CIR model was once touted as an improvement over the Vasicek model because it did not allow negative rates. And while it’s less clear what initial circumstances would trigger a huge drop in long-end break-even inflation, there is a tipping point beyond which those rates could accelerate downwards.

Pension payments are typically linked to inflation, but DB pensions can’t be cut even if inflation is negative. Most often, the increases are also capped, normally at 5%- this is LPI0-5. That means each member is implicitly short an option at 5% and long an option at 0% (and the scheme’s exposure is the other way round). These are options so they have deltas, i.e. they do not move one-for-one with RPI. Intuitively, if 10y inflation were 8%, the cap would always be hit, and there would not be much sensitivity to inflation moving up to 9% or down to 7%. By extension, the sensitivity to inflation changes as inflation moves up or down.

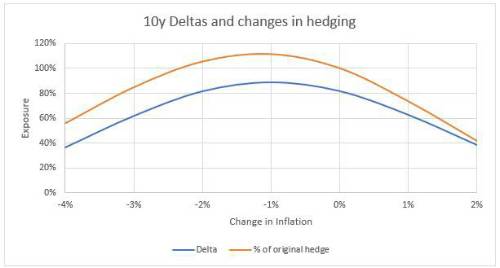

We show this effect in two ways. Using a standard model (Black-Scholes with 1.5% volatility), we first calculate the deltas of 10y LPI0-5 to RPI (i.e. if RPI moves 1bp, how much does LPI move?). We then also calculate a hedging benchmark today (i.e. the RPI cashflows built today to match the inflation sensitivities of the liabilities), and look at how much this would scale up and down if inflation changed.

The exact details depend on the model used, but the bigger picture doesn’t. Since inflation is closer to 5% than to 0%, a small move down would lead to greater sensitivity, and DB schemes buying more inflation . However, for a very large fall in inflation, the floor would be closer than the cap. In this scenario, as inflation fell, so too would sensitivity. Even ignoring collateral impacts, if long-end inflation fell below around 2% there would be a risk of a reinforcing feedback loop whereby falling inflation prices led schemes to reduce inflation exposure (i.e. selling inflation), causing prices to fall further. The mechanism is there.

There are ways to mitigate and manage this risk, and others like it. It’s also not especially likely. But it is precisely the sort of tail risk which could derail even a well-funded, well-hedged scheme.

1 With a symmetric model like Black-Scholes, the highest sensitivity will be when inflation is in the middle, at 2.5%. With a skewed model this peak could be off-centre, but the delta will still be higher at 2.5% than at (say) 4.5%.

|