By Beat Habegger & Kaspar Zellweger, Swiss Re Political Risk Management

Events and developments of the past months have forcefully reminded the insurance industry of political risk. First, the unsustainable public debt burden of Eurozone countries and the political battles around both the bail-out packages and the raising of the US debt ceiling highlighted how much the international financial markets can depend on political agendas, decisions and actions. Then, the immolation of a vegetable vendor in Tunisia triggered a wave of revolutionary upheaval across the Middle East and North Africa that brought down governments and cast a long shadow over energy security to the global economy. Last, the riots in UK cities produced significant insured losses and put the lurking socio-political risk of alienated youth into the spotlight.

Insuring and modeling political risk

Political risk is a term that comes with different shades of meanings and academics and business practitioners have long searched for viable definitions. In a broad sense, political risk is a “macro risk” – a risk of risks – and as such part of the wider setting in which the course of business is taking place. It is about war and peace, sanctions and corruption, the quality and predictability of the rule of law, or the effectiveness of governments and the reliability of their commitments. As such, political risks are rather unspecific and do not match the traditional criteria of insurability. They are also challenging to model due to the difficulty of unambiguously coding events, establishing clear cause-effect links, or determining and calculating “losses“.

However, in a narrower understanding political risk applies to numerous phenomena, events and actions of a political nature or caused by political actors, which can trigger life and non-life covers and result in insured losses. Terrorist acts, for instance, produce losses in many lines of businesses, while specific lines of business like Marine indemnify for losses from events that are political in nature (e.g. war), though within tight limits and with defined exclusions to control accumulation. Moreover, the insurance industry has developed its own “political risk insurance (PRI)” as a derivative of credit insurance products, covering such events as confiscation by host governments or non-payment by sovereign obligors.

Repeated efforts have been made at modeling this latter type of political risk, but with mixed success. Political perils of this nature tend to be “lumpy” and heterogeneous, making it difficult to have a portfolio of homogeneous events. Expected loss is difficult to estimate, calculate and often also locate, and loss events are not purely accidental, but open to human agency. Therefore, when insurers offer cover for political risk, whether under PRI or in the more conventional lines of business like life, health, marine, aviation or even property under buy-back or add-on clauses, such as Strikes, Riots and Civil Commotion (SRCC), they have to rely as much on qualitative underwriting information as on quantitative and historical data.

Embedding political risk management in the organization of an insurance corporation always poses a challenge. It requires a cross-functional approach, making the management of those political perils which are underwritten as part of a line of business’ standard product offering also part of that respective risk management. In addition, a small specialized political risk unit can adopt an advisory and expert role when it comes to the identification, mitigation, monitoring, and reporting of political risks on an aggregate level. This implies good and trustful working relations with other central functions, like macro- and industry-specific economic research, regulatory affairs, legal, compliance and other risk management functions as well as the business Timely, actionable advice and information are crucial in supporting the business in managing political risk.

Focusing on social unrest

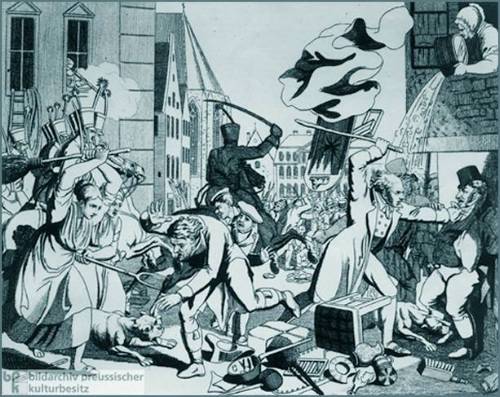

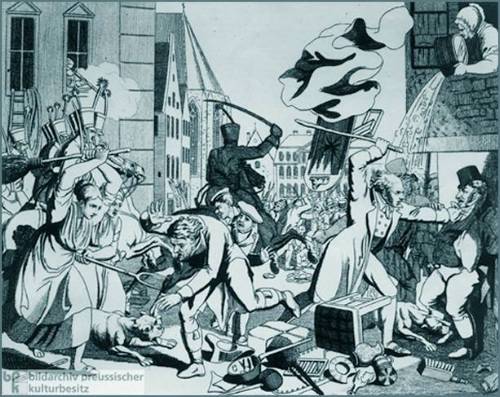

Social unrest has long been covered by property insurers in many jurisdictions. Social unrest often has a political leaning as it may be, for example, provoked by ethnic tensions or by protests directed against the government’s economic policies. Historically, there is a degree of correlation between economic hardship and the occurrence of upheaval in the streets, although no clear, linear causality exists. The concrete reasons for the eruption of social protests and why they turn violent are highly diverse. Single-incident events, long-term socio-political and demographic trends (e.g., urbanization or ghettoisation), but also national historical legacies influence the frequency and severity of civil disturbances.

Since the onset of the sovereign debt crisis, peripheral Eurozone countries have seen an increasing amount of social protests. They were directed against fiscal austerity and reform programs, but voices rallying on more extremist agendas have been marginal and protests remained mostly peaceful. This contrasts with the recent riots in the UK which were triggered by the police shooting of an individual. While the government’s cut-backs in social expenditure may have been a contributing factor to these riots, their outbreak had more to do with the long-term decay of the social fabric and cohesion in a number of marginalized, urban communities and the alienation of some segment of youth than with the politics of the day or opposition against specific government policies. In fact, there was no overt political message or meaning to the riots, but only wanton destruction and plundering.

Violent social unrest can be expensive to the insurance industry. The ethnic riots in Los Angeles in 1992 resulted in an insured loss of USD 775 million. Riots in Jakarta after the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998 cost USD 250 million and the French protests in 2005 reached the amount of USD 193 million. Estimates for the costs of UK riots in August are still preliminary. According to the Association of British Insurers, it could amount to USD 320 million. The impact for the insurance industry may be further contained, however, due to a government ruling subrogating insurance claims to the police.

Outlook on political risk: not off the map

A look at the state of the world in 2011 nurtures the impression that political risk, whether in the broad or the narrow sense, will remain with us for a while. It will pose major challenges to the balance sheets of insurance companies – both on the asset and the underwriting side. Social unrest and violent protest, leading to property and other insured losses, are potentially part of this picture, particularly also in the Eurozone where insurance penetration is generally high (though it is lower in the peripheral countries under the biggest economic pressure than in the wealthier parts of Western and Northern Europe). Meanwhile, insurance penetration is growing rapidly in a number of emerging markets that are not free of political risk and also face dangers of social unrest. Underwriting political risk and covering political perils in specific lines of business, as well as monitoring, managing and mitigating political risk on a corporate level remain a challenge for the insurance industry as whole as well as for individual companies.

1.Jarvis, Darryl S.L., and Martin Griffiths (2007), ‘Learning to Fly: The Evolution of Political Risk Analysis,’ Global Society: Interdisciplinary Journal of International Relations, 21(1), January, pp.5-21

2.See, for instance, http://www.slideshare.net/athula_alwis/Combined-Credit-and-Political-Risk-Paper

3.See, for instance, Raoul Ascari. “Political risk insurance: an industry in search of a business?”SACE .Working Papers Nr. 12, pp. 23f.

4.Swiss Re sigma Catastrophe database (inflation-adjusted 2011).

5.Best's Insurance News.

|